Bridging concepts and reality with Evidence-based Designs

"I believe that the way people live can be directed a little by Architecture”

When Tadao Ando quoted the words, the relationship between Architecture and Man was only beginning to come to light.

Although Architecture brims from the fact that our mind is wired to interact with a space in a certain way, it has been constantly subjected to the question of rationality and given the label of imagination and whim whenever a new concept is involved—loose-ended research studies, non-validated claims, and far-fetched concepts challenge the acceptance of new ideas not only by the common population, but also by other subject experts involved in a space’s creation. Such challenges to ground-breaking concepts have made way for a new line of thought called “Evidence-based Design” that explores and brings out the real side of hypothetical concepts, making them less anticipatory and more reliable. While the concept began as a literary context in pieces like John Zeisel’s Inquiry by Design (2006)—a book that talks about psychological and neurological responses to built environment; EBD evolved into the practice of Architecture when sensitive designs like that of healthcare facilities demanded illustrative evidences to support the vision of their design.

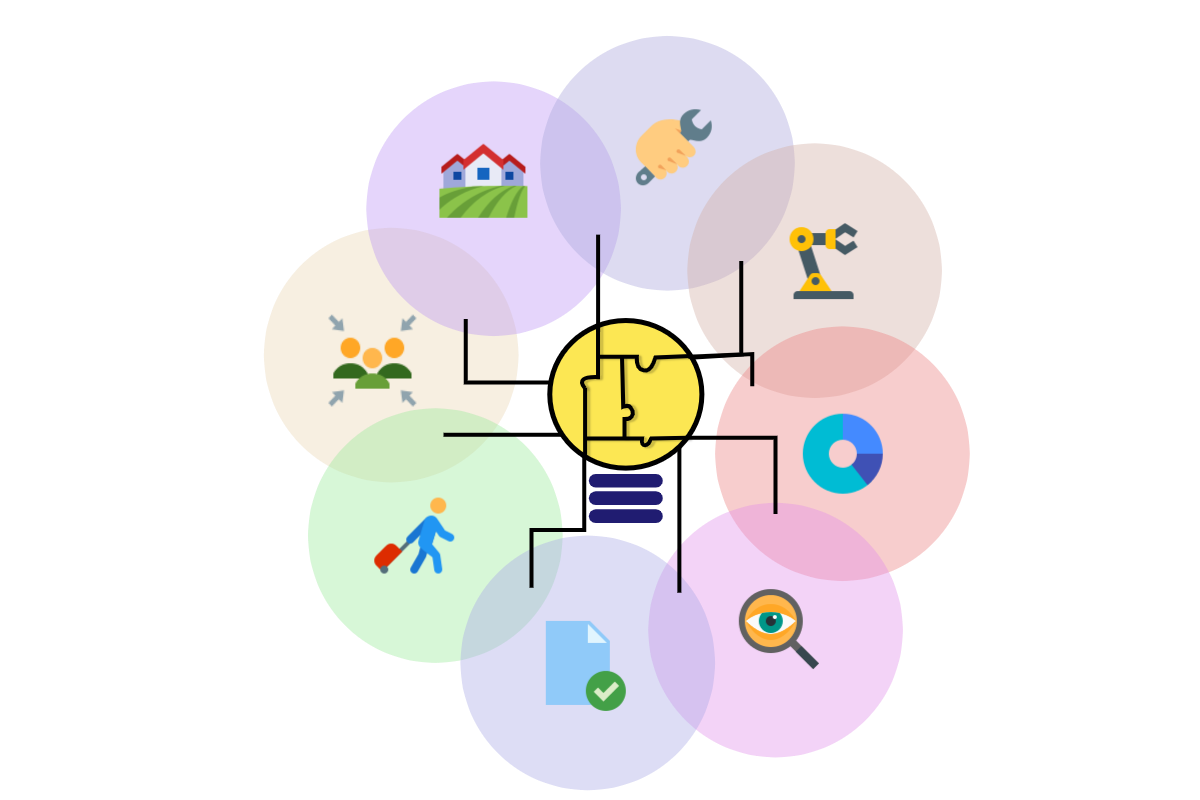

Evidence-based design (EBD), by definition, is a structured approach that brings the best outcomes for a space from credible research that offers liability on the whole. The core of this approach is built around the user-space relationships that are typically intangible and theoretical by nature. EBD validates these psychological relationships with social experiments, survey data, custom-created assessment tools and more empirical methodologies that prove a concept’s stance in real-time.

Designing for reality with evidence-based design

Image source Credits: Pixabay

Over the years, the foundation of architectural practices is built on time-tested methods that have emerged into new areas of focus in architecture—while international architects like F.L. Wright created concepts that reunited buildings with nature, Indian architects like Laurie Baker redefined comfort with a building’s climatic resilience. The ideologies of such revolutionary architects relied majorly on collective evidences like client psychology or construction methodologies that were constantly subject to “trial and error” to come into practice. An elaborate articulation of these trial and error experiments takes the main role in Evidence-based design that blurs the boundaries between research and practice, thereby devising a holistic approach that can be relied on by architects right from the conceptual phase of the design.

Yet, it cannot be ignored that the fine line between architectural conceptualization and reality lies in understanding of the variegations—understanding user responses along with their demographics, cultural differences and other models of diversification of users have an indirect effect on the user-space behaviour. Such in-depth analysis gives a better look into a behaviour-based design that aims to interact with the user and provide an immersive experience that stimulates the users. An ideal example would be the inclusive design of a school campus that caters to the needs of a diverse student population, or healthcare facilities for special children or rehabilitation centres for differently-abled people. The unique needs of these user groups call for a deeper understanding that encompasses interdisciplinary studies under Evidence-based principles—a practice that can make the users feel safe and included, and free them from any phobia.

In parallel, Evidence-based design also provides a fine medium for new design interventions such as user controls as in automation technology, digital locks, gesture controls and more that achieve the possibility of connecting with a user along a different (digital) dimension. From a sustainable point of view, Evidence-based design helps in decision-making—in the choice of befitting energy-efficient systems, micro-climate-responsive materials, waste reduction mechanisms and more than can be validated from past studies or present data collection and incorporated into a space to get the desired outcomes. These data or evidences have the potential to strengthen the base of any design proposal, in any area of focus.

Comparing sensorial experiences with factual studies

Image source Credits: Vusal Ibadzade

Psychological and sensorial effects are intangible elements that form the crux of any concept in architectural design. These facets of spatial experience stimulate the users with a consciously-crafted space that re-thinks the regularity of design—redefining layouts and seating arrangements considering the social behaviour of the users, introducing easy access points to avoid breaking the continuity of an experience, the inclusion of natural light for enhanced mood in the setting, buffering or filtration of sound for infusing the sense of privacy, leveraging the use of the space’s expanse to create an inviting character and more theories that can be proven with the help of tried and tested methods or evidences. The final design is articulated along the interests, lifestyle, abilities and fears of the users that are backed by these evidences, in a well-structured process—from primary evidences like a patient’s bereavement needs in a palliative care centre or a prisoner’s moral needs in prisons, to secondary evidences like an employee’s work culture based needs in workplaces or a student’s mental health needs in school premises, Evidence-Based Design has grown to exhibit a constructive character to the existing practices in Architecture.

Validating concepts with Evidence-based results

Image source Credits: Enrique Hoyos

Evidence-Based Design is rooted to the validity of the evidences that is ensured by an elaborate process going beyond literature studies. It begins with a meticulous documentation process that includes suggestions from the key user groups in the form of surveys, questionnaires or experiments such as observational studies or random/controlled trials with the end users. It is backed by literature studies that include analysis and comparison with existing reports, project references or design standards that are found ideal for the design context. This phase also involves consideration of a number of operational factors including the calculation of initial investment involved for research, scheduling of board meetings with other professionals, execution of the design solutions with available resources etc.

The study process is followed by peer reviews that extend across the design process that are discussed and approved by all experts onboard. The process also involves approaching different governing bodies for comparison with their latest standards—minimum area requirements of different spaces, standard layouts, clear height, furniture clearances and other ergonomic limitations are bound for approval from the existing book of standards. A conclusive report is made to present the evidence-based results as reference materials, followed by design mockups, for seamless execution under multiple professional teams involved in a design process. Certain methods also involve post-occupancy studies and trials that evaluate the user responses and reflect on the findings of the research process. These results are open to be published in journals or established as academic teachings that shall benefit all of the professional community in the future.

Architects like Magda Mostafa came into the practice of Evidence-based Design through design projects that challenged regular architectural standards and evolved their own book of standards as evidences of their research—her design for Egypt’s first educational centre for autism created an interactive space for children with autism based on their activities, psychological responses and more that she later complied Autism ASPECTSS Design Index. Similar efforts were also taken outside healthcare design, by architects like Lone Wiggers who employed evidence-based design tools to study the relationship between student performance and daylight permittance in schools—the studies also revealed interesting observations on how the orientation of the windows improved analytical abilities compared to others. She has taken up modern channels such as design symposiums to share knowledge and present evidences to the architectural community across the globe. Many other contemporary architects are representing evidence-based design at different parts of the world to pose this as the next big thing in architecture.

Scope of EBD in mainstream architecture

Image source Credits: Pixabay

Since the beginning of time, EBD has struggled with acceptance among the architectural fraternity, given the increased cost and time invested in the research process that failed to keep up the pace with the challenging projects of today. To outweigh these limitations, EBD has constantly evolved the tools and techniques with digitization, strategic planning and more that provide a feasible approach to the undeniably significant side of EBD in mainstream architecture.

Amidst the past debate, EBD was continually seen as an essential part of behavioural design models prevalent in healthcare design—hospitals, rehabilitation centres, women care centres, palliative care centres and other clinical facilities have been widely benefitted by architectural concepts that resonated with the ideologies of the medical practitioners. The practice helped the designs evolve as inclusive spaces that streamlined the circulation of staffs and patients, improved wayfinding for new visitors, introduced private rooms to involve family care in the treatment and made the entire process come under a practical framework with decentralised nurse stations and strategically distributed monitoring systems that provided a better, smarter environment for medical support. In addition to this, EBD also curates the spaces along the concept of well-being—such as workspace design that focuses on better productivity and low stress levels, campus design that focuses on boosting creativity and alleviating social anxiety, among others.

With time, EBD is expected to be a catalyst for creating the architecture ripple effect that supports the idea that buildings have a bigger impact on the surrounding—the structures in the immediacy, the population flowing through the space and the social-cultural impact created in the neighbouring zones. This ripple of a space’s impact is one of the major topics of discussion among the young architects of today that is likely to revolutionise the design practices of tomorrow. When ideated along the evidence-based principles, such revolutionary ideas are given a stage for becoming the hope of the future—a future that we all can rely on.

Cover Image source (edited) Credits: Adrian Gallo

About Author:

Akshaya Muralikumar is an architectural writer and media strategist who believes in the power of storytelling in instilling meaning into the spaces. Coming from an architecture background, she has taken a detour into the world of content, travelling its different spheres with blog articles, web content, magazine features, newspaper publications and more that keep her engaged in both digital and print media. Under the personal brand @voice_dot_m, she is set on a journey to experiment and explore on and beyond Architecture, to its specializations and allied subjects, with an editorial edge.