Edges and Its Conflicts

Figure 1 Mining in India, Source: The Energy and Resource Institute (TERI)

Edges; also understood as boundaries and extent of habitats/ecological zones, is a concept in ecology. It is used to explain the earth’s diverse ecology, its dynamics and transitions from one ecological zone to another. Edges are affected not only by natural phenomenon but also due to human activities, one of those activities is mining. While mining activity boosts many aspects such as economic growth, job generation and infrastructure development; anticipating change in edges caused due to mining should also be an important consideration. The article aims to highlight the importance of edges and its direct effects on human and animal lives. The mining activities fragments elephant habitat in Central India causing habitat destruction and rise of Animal- Human conflict.

Figure 2 Map showing boundaries of states in Central India, source: Google Earth

Ecological edges

The concept of edges was developed to categorize and understand Earth’s diverse ecology; defining different habitats/ ecological zones and their overlaps. It brings a great level of insight in the field of ecology as edges exists in all ecologies ranging from micro to macro zones. Due to dynamic and diverse nature of earth, over time ecological zones are transformed in shape and size and some new ecological zones are also observed. This is a common phenomenon that regularly takes place in the earth’s ecology and it is evident through changes observed in Edges; the natural phenomenon is referred to as Edge Effect (Murcia 1995, Ewers & Didham, 2006).

However, due to human activities, the concept of the Edge Effect which is primarily an ecological one, transcends into socio-ecological issues. Habitat destruction caused by human activities is an example of the same phenomenon.

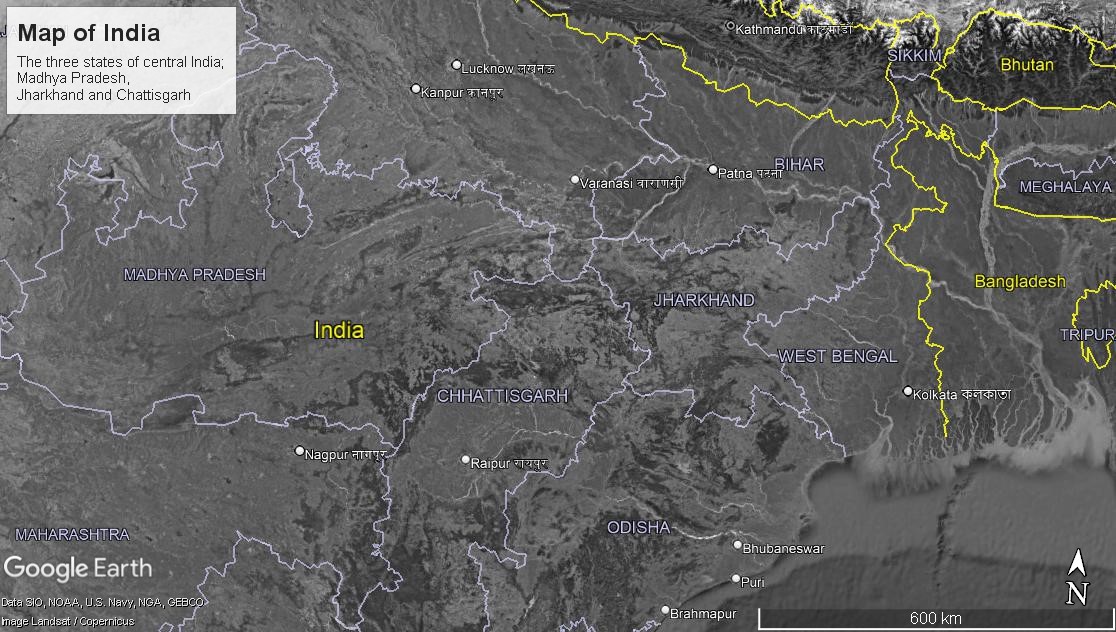

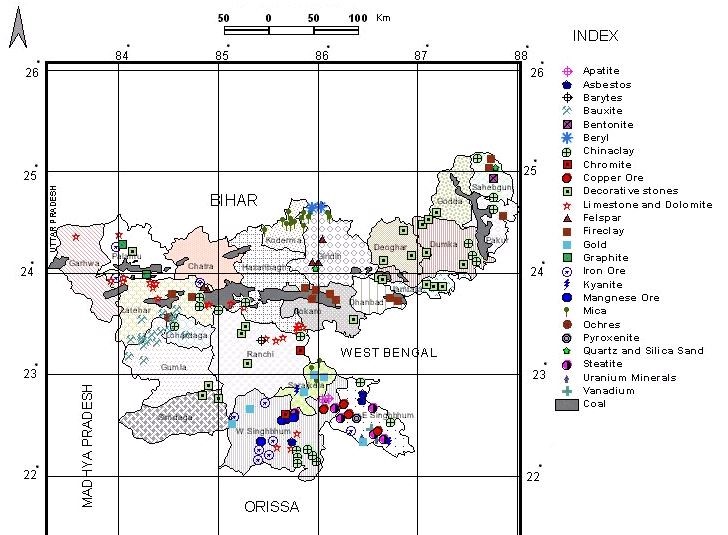

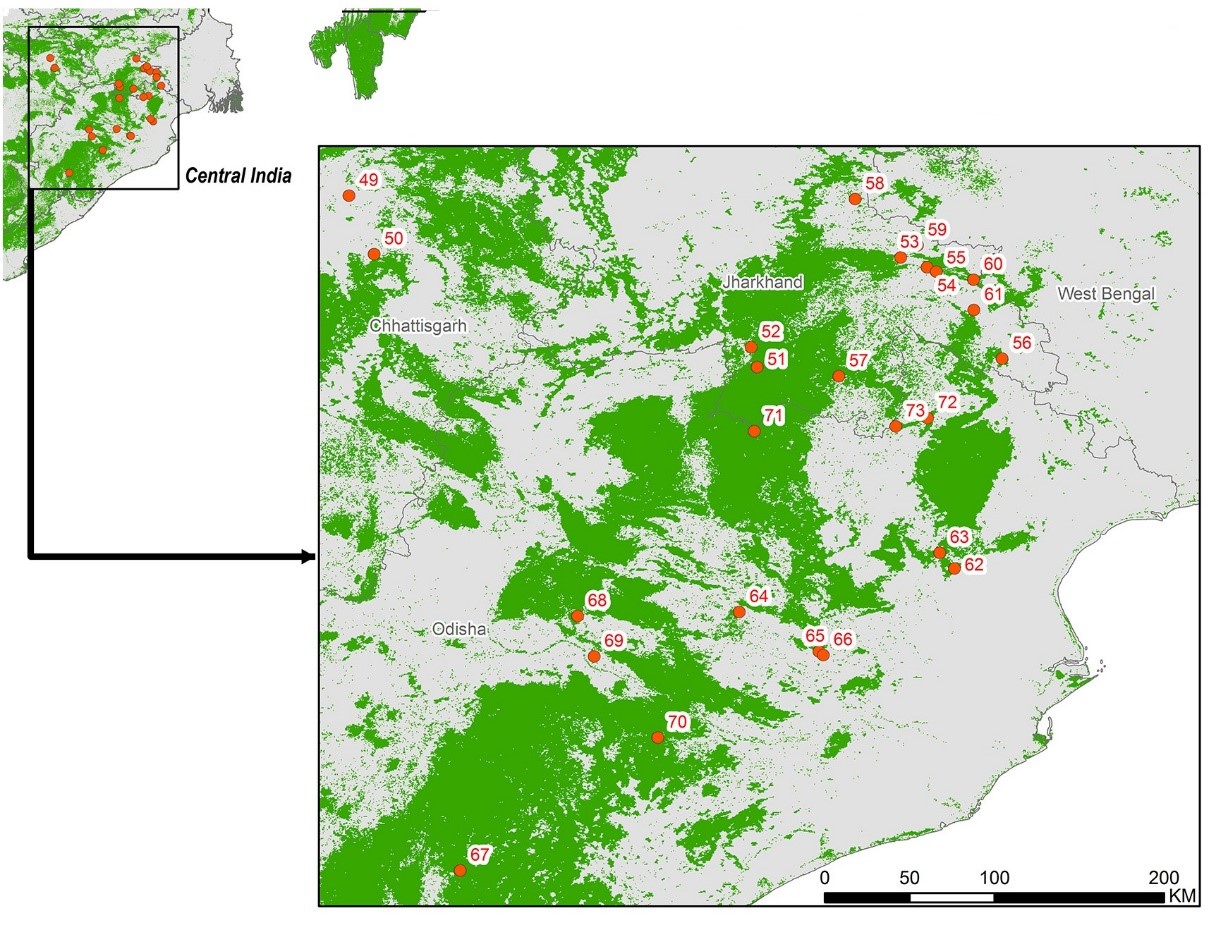

Figure 3 Mining in Central India, source: Government of Chattisgarh

Economy in Central India

Central India is known for its minerals, mining and quarrying are primary contributor to the region’s economy. For India, mining and quarrying sector contributes to around 2.5% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As of FY21, the number of reporting mines in India were estimated at 1,229, of which reporting mines for metallic minerals were estimated at 545 and non-metallic minerals at 684 (Source: IBEF). There are seven major mining states in India out of which 3 fall in Central India. Thereafter, a large amount of activity and traction in Central India is observed in the mining sector.

However, this traction has caused the growing contention between mining and elephant habitats. If one does a quick search on the Central India’s Elephant Habitat, an overwhelming number of articles and papers appears, all pointing to one issue—the destruction of the elephant corridors due to mining. Hence, activities for mining from depths of earth disturbs the edge of animal habitat on its surface.

Figure 4 Mining in Central India, source: DNA India

Figure 5 Mineral Map of Jharkhand, source: Jharkhand State Mineral Development Corporation Ltd.

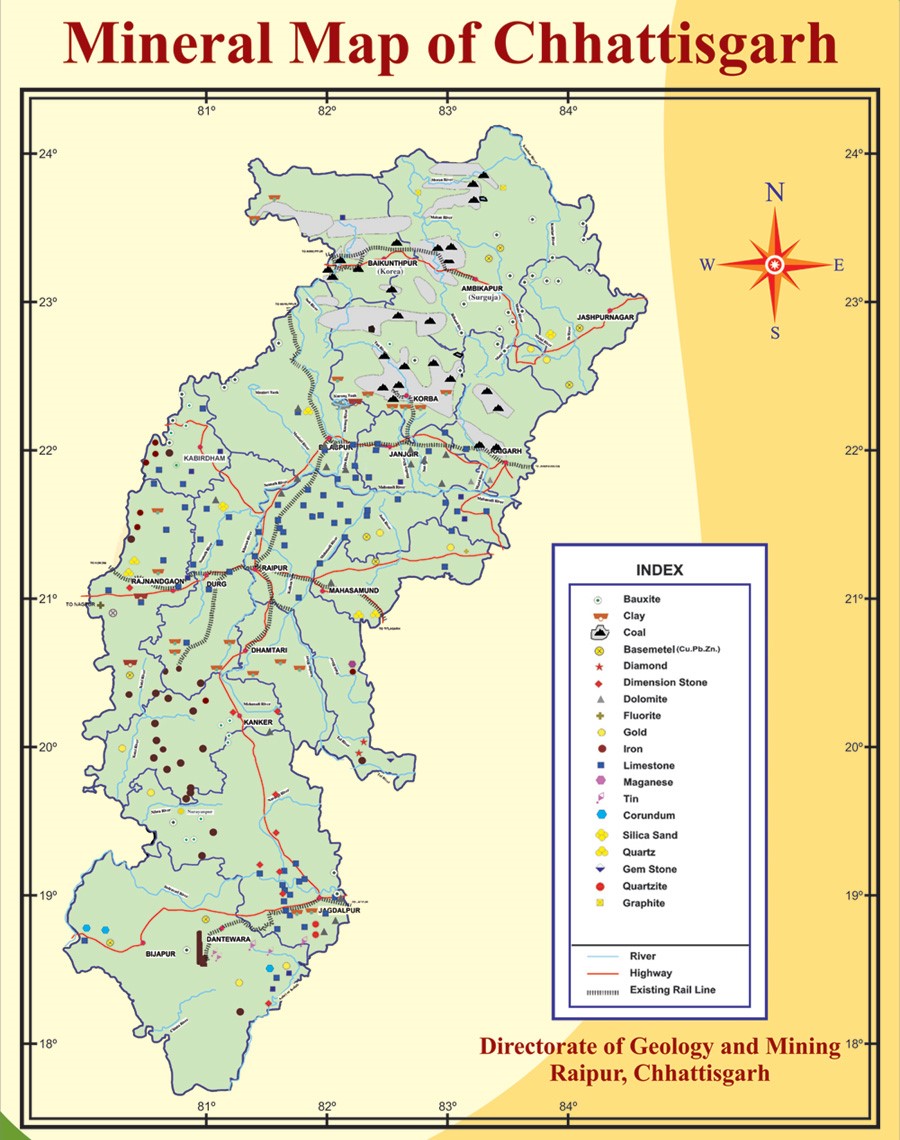

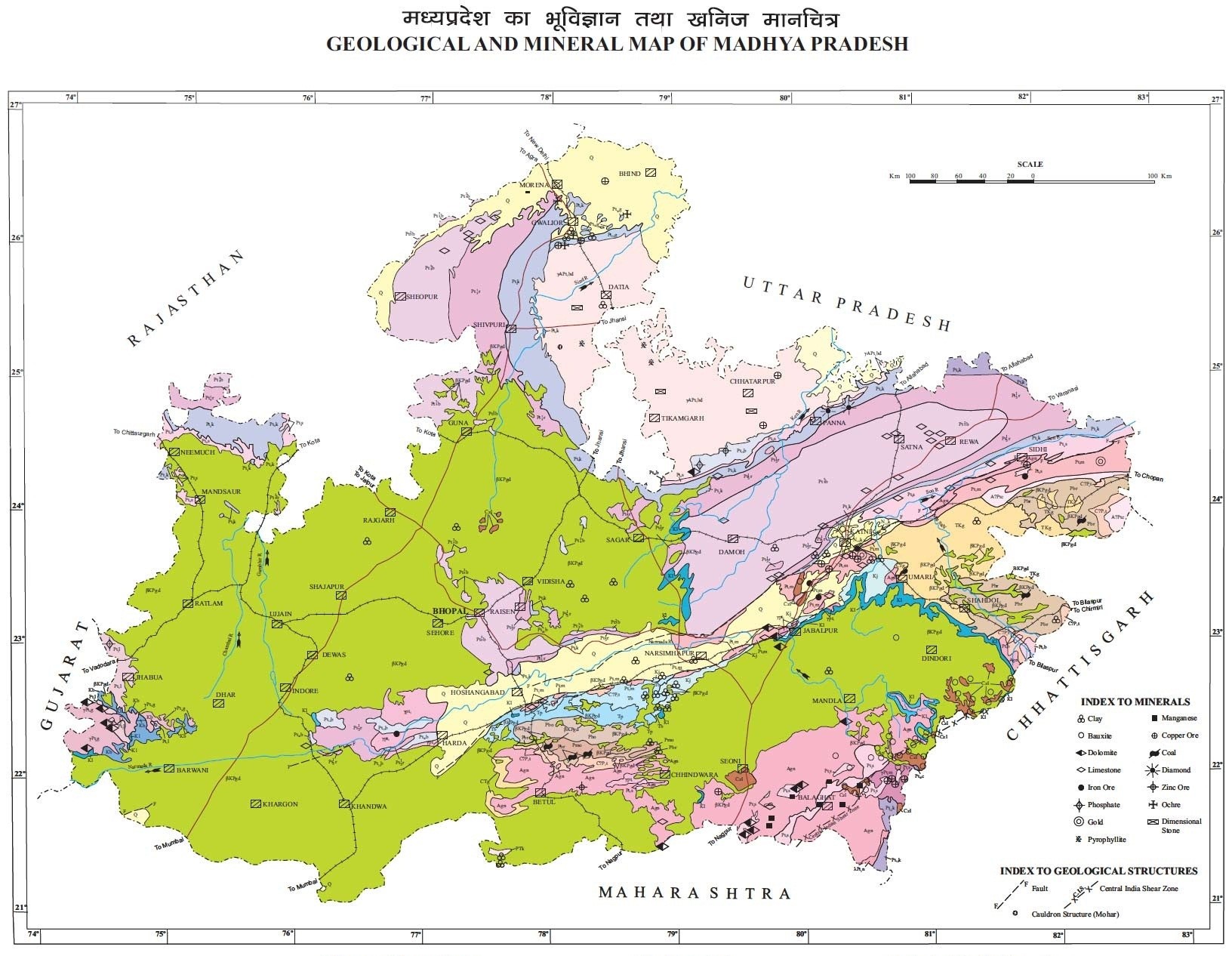

Figure 6 Mineral Map of Chhattisgarh, source: Directorate of Geology and Mining, Chhattisgarh

Figure 7 Mineral Map of Madhya Pradesh, Source: Government of Madhya Pradesh

Violation of Edges

A new mining project, which is approved without wholistic environmental assessment, abruptly destroys the habitat and ecosystems instead of smooth transitioning, resulting in violated edges, creating an edge effect. The linear infrastructure of roads, railways and canals built to aid the activity of mining and its subsequent development, divides an existing ecosystem starkly by introducing a new rigid artificial edge. These activities, abruptly breaks the habitat and creates High-contrast ecotones (a narrow transitional zone) on all sides surrounding it. Elephants then either succumb to the edge effect by dying in the High-contrast ecotones due to lack of food and shelter or move away from it.

Moving away causes them to interact with a new habitat, (sometimes human settlements, farms or villages), thereafter destructing the edge of the new habitat; the rise of the Elephant-Human conflict is then observed.

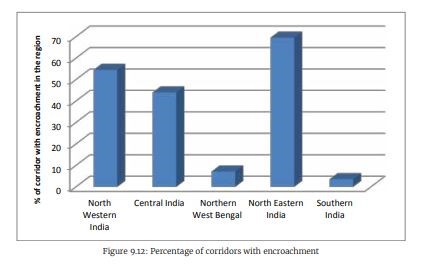

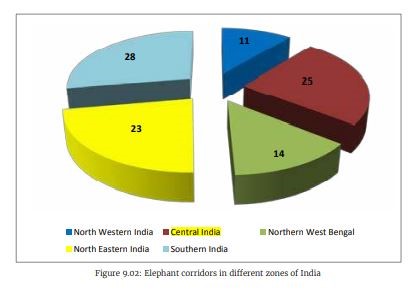

Percentage of corridors in different zones of India Percentage of Corridors with encroachment

Source: Conservation Reference Series No.3 Wildlife Trust of India, New Delhi

Villages, those lie near the area of Elephant-Human conflict, suffer great loss in livelihood and lives; elephants that are forced to migrate, ruin farmland and unintentionally attack humans. Such violation of edges causing edge effect has negatively impacted the lives of both the elephants and humans

The article was inspired by a reporting done by Mongabay India; two people from the village, who went to pick mahua flowers (which is one of the source of income for the villagers) early in the morning on April 5th 2022, were killed in an elephant attack.

“We hardly make a living from farming, but we can fulfil our hobbies by picking mahua. With the earnings we get by selling mahua, we buy clothes etc., every year. But this year, we are afraid to go to the forest,” said a resident of Masiyari village to Mongabay.com India (Mishra, 2022)

Figure 8 In 2018, a herd of about 40 elephants moved from Chhattisgarh to Madhya Pradesh, and it was the first time that the state had an elephant colony. Photo by Alok Prakash Putul, caption credit (Mishra 2022)

Here two edges are of paramount important; edge between mining area and elephant habitat and edge between elephant habitat and human settlements. Violation of these edges due to mismanagement, lack of understanding and consideration, has caused the edge effect to unfold. Two key issues result in the mismanagement of these edges; gaps in impact assessment and underrepresentation of locals.

Gaps in Impact Assessment

Any new mining project impacts people and the environment near it. Thereafter, to assess the impact, four Acts govern mining activities in India.

MMRDA (Mines and Minerals Regulation and Development Act 1957) and Mines Act 1952 are the legislations on mining in India. Forest Conservation Act 1980 and Environment Protection Act 1986 enacted for the protection of forests and the environment are also applicable to mining (Raj & Ahmed, 2019).

Two main studies are conducted under these acts, one that assesses the environmental impact (Environmental Impact Assessment Report) and one that assesses the project-affected people (Study conducted under District Mineral Foundation).

1-Environmental Impact

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Report is conducted at the beginning of any major development project. A proposal is submitted with a land-use map that embarks the beginning of the process.

The following steps include; Screening, Scoping, and Consideration of Alternatives, Base Line Data Collection, Impact Prediction and Assessment Of Alternatives, EIA Report, Public Hearing, Decision Making, and Monitoring of The Clearance Conditions (Raj & Ahmed, 2019).

This process might seem extensive and virtually appropriate for the EIA. However, it is criticized by many scholars for its lacunas, those of which largely lie within the implementation process of the act.

Raj and Ahmed, both scholars from Aligarh Mumbai University list the following points of major gaps in the EIA of mining (Raj & Ahmed, 2019):

- Inaccurate and incomplete data & non-adherence to scientific methodology. There is a conflict of interest as the project proponents get the EIA conducted. Fabrication, repetition of old information, or avoiding crucial rather more important facts

- Most often smaller areas (less than 5 hectares) are excluded from the requirement of an EIA, leading to unchecked mining and exploitation

- Assessments are poorly time and fail to remain holistic.

- Poor implementation and lack of inappropriate monitoring have left the EIA process as a mere administrative formality

2-People affected

The people affected by mining are addressed by the District Mineral Foundation (DMF). DMF is a trust, assigned to identify mining-affected people to improve their lives and livelihood (DTE, 2019). These mining-affected people are known as 'beneficiaries'.

Currently, as per the PMKKKY (Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana) guidelines for DMF Trusts, mining-affected people include:

- Affected family, as defined under Section 3 (c) of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013

- Displaced family, as defined under Section 3 (k) of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013

- People who have 'legal and occupational rights' over the land being mined

- People who have 'usufruct and traditional rights' over the land being mined v. Any other as appropriately identified by the concerned Gram Sabha.

The list of beneficiaries is not accurate due to faulty data collection or using old list from other projects. The norms for being qualified as mining affected does not cover people who are indirectly affected by mining (DTE, 2019).

The inclusion of people who are impacted due to the Elephant-Human conflict in the area remains unclear. Almost all the peripheral tribal communities in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh have lost lives and livelihood due to the ongoing Elephant-Human conflict in central India. These communities are as much 'mining-affected' as are those who are directly displaced when land is acquired for a mining project.

Underrepresentation of Locals

The locals of the villages that reside in these areas are the first in line to be impacted. They first-hand experience the causes and impact of edge effect. Take the case of Masiyari Village in MP; the villagers have not only lost human lives but also suffered instability in their livelihoods.

The understanding of edges is more with locals; policy makers should use knowledge and expertise of locals to assist in the process of edge management. To understand the causes and effect of the edges, it is crucial to involve locals in the management of edges.

However In 2022, Forest Conservation Rules have been modified in a way that violates the Forest Rights Act (FRA) (DTE, 2022)

As a result of the modification, private developers can remove forests without obtaining the permission of the Gram Sabha, the village's elected body. Excluding the Gram Sabha from the equation essentially removes the representation of the locals, who are the first in line to be impacted by any new developments.

Edge management through Eco-sensitization – A way forward .

Ecology as a scientific field, has developed the concept of edges, edge effects and ecotones to a great depth. To address the issue of mining in Central India and its peripheral effects, it would be greatly helpful to take this ecological concept and apply for edge management.

When a new mining location is proposed, an analysis of edge effect and ecotones must accompany it. Locals not only from the immediate surroundings but from region who will be directly or indirectly affected, should be consulted for ground reality. The report should look at the land, habitats, communities, and ecology by marking their edges, defining their ecotones (transitional areas), and addressing any and every shift in all edges observed.

Mining, saving habitat and resolving animal human conflict are crucial elements at play. It would help greatly if the issue is looked at through the science of edge effect and ecotones.

Edge Identification:

WTI (Wild Life Trust India), under the study named ‘Right of Passage’ has marked edges of 108 elephant corridors and recommended for their preservation and management. Many of them are in Central India and require to be protected and conserved for the Elephant Habitat. The recommendations from the report also include no new mining projects and discontinuation of development projects in the identified zones, habitat restoration of the degraded and mined area in the corridor are also recommended (Menon et al., 2017).

Using this kind of study as basis, the changes in edges can be anticipated. Remedial measures and alternatives for smooth transition of edges can be planned.

Figure 9 Elephant corridor map of India, source: World Resource Institute, 2017

Impact assessment and remedial measures

The process of Impact assessment must consider the following points:

- A new mining project setup impacts not only its immediate surrounding but also its nearby region. Case in point: Masiyari Village of MP has been negatively impacted due to mining activities in Chhattisgarh.

- Habitats and Ecology do not understand state boundary, they operate through ecological zone; an impact of a certain activity in a certain state can have an unprecedented impact on another state. The authorities must look past state political boundaries and address the boundaries of habitats and ecology to truly assess the impact of any new mining project.

Involvement of locals:

- Locals must be consulted when a new mining project is proposed. As it is clearly evident from the cases of Animal-Human Conflict, human settlements are negatively impacted due to mining activities.

- In impact assessment, survey and identification of people affected must be conducted, humans impacted due to Animal-Human conflict must be included as ‘Project affected people’. These includes locals from mining areas but from the areas which will get directly or indirectly affected.

- Negotiations must be conducted with the locally elected representative body as a part of impact assessment and control.

Mining cannot be stopped, it is an important contributor in the economic sector; however, it can be regulated; it MUST be regulated through land management. Land management, then, may be done through the science of edge effect and ecotones.

The key idea is to look at the issue as a socio-ecological one and not a tussle between the free markets versus traditional conservation. Understanding of edge effect can assist the process, by allowing us to view the crucial ecotones (transition zones between zones) as areas of concern.

It must look at ways to create soft contrast ecotones (broad transition zones), to minimize destruction to habitats, communities and ecology.

Land management, and eco-sensitization is the way forward if India wishes to continue to benefit from mining as a growth source of GDP and in parallel conserve habitats and communities that are directly impacted due to the same.

References:

DTE. (2019). Districts must identify mining-affected people to keep DMF funds targeted. Down To Earth. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/mining/districts-must-identify-mining-affected-people-to-keep-dmf-funds-targeted-65230

DTE. (2022). Forest Conservation & Consent: How gram sabhas halted risky projects in the past. Down To Earth. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/forests/forest-conservation-consent-how-gram-sabhas-halted-risky-projects-in-the-past-83717

Ewers, R. M., & Didham , R. K. (2006). Continuous response functions for quantifying the strength of edge effects. Journal of Applied Ecology, 43(3), 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01151.x

Government of India, Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana) guidelines (2015).

Indian metals and mining industry analysis jul 2021: IBEF. India Brand Equity Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://www.ibef.org/archives/industry/Metals-and-mining-reports/metals-and-mining-presentation-july-2021#:~:text=As%20of%20FY21%2C%20the%20number,world's%20second%2Dlargest%20coal%20producer.

Menon, V, Tiwari, S K, Ramkumar, K, Kyarong, S, Ganguly, U and Sukumar, (2017) R (Eds.). Conservation Reference Series No. 3. WIldlife Trust of India, New Delhi.

Mishra, M. C. (2020, October 2). Conflict increases as elephants from Chhattisgarh move to M.P. Mongabay. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://india.mongabay.com/2020/09/wild-elephants-in-madhya-pradesh/

Mishra, M. C. (2022, April 27). Spirits are low this mahua season as fear and grief take over these MP villages. Mongabay. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://india.mongabay.com/2022/04/spirits-low-this-mahua-season-as-fear-and-grief-take-over-these-mp-villages/

Murcia, C. (1995). Edge effects in fragmented forests: Implications for conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 10(2), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(00)88977-6

Raj, A. A., & Ahmed, Z. (2021). Environmental impact assessment of mining in India: A review of legal and institutional mechanism. Environment Impact Assessment, 339–351. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003198208-20

Singh, R. (2022, February 18). Elephant corridors impacted as mining expands in Jharkhand. Mongabay. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://india.mongabay.com/2022/02/elephant-corridors-impacted-as-mining-expands-in-jharkhand/

About Author:

Saba Serkhel:

Saba is an architect-planner from Mumbai City. Educated in India and USA, she is interested in exploring social issues which can be resolved through planning and architecture interventions. As a passion project, she also has a podcast created with a friend. Their podcast discusses urban planning issues that are neglected in mainstream academic spaces, titled “Lettus Talk”. Saba also makes comics exhibiting her work on the social media handle @saba_serkhel. To present her thinking efficiently, Saba explores avenues of expression through various mediums. Reach her at serkhels@gmail.com