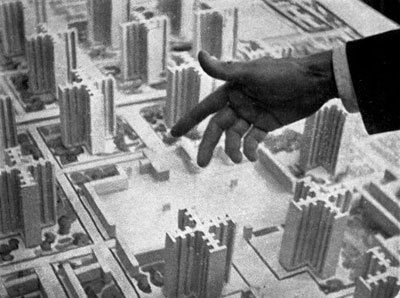

Mumbai Maximum City Under Pressure

Our FILM , “Mumbai Maximum City Under Pressure”, takes its name from the notion of that conceptual hybridity between a boundary and infinity, location and imagination, memory and discovery.

Mumbai, as a city lends itself to the tempting construction of binaries. Perhaps U-TT’s most frequently visited horizon is the blurry line between formal and informal. While simplistic definitions of this binary can be summarized as top-down development versus bottom-up growth, U-TT sees a more nuanced picture.

Informality is not a lack of form or order (that would be non-formality), but rather the state of being in formation. It is the constant introspection of forms through trial and error, the refinement of forms through spontaneous experimentation rather than static acceptance of tradition. And above all, informality is perhaps the process of getting past modernity’s fetish with form itself by denying form static supremacy. The horizon between formal and informal is a horizon of processes rather than products. The difference between the two is one of perspective. This is appropriate, as horizons are also inherently about orientation, marking one’s present position in relation to where one was in the past, or will be in the future. The setting sun is a sign of both the day that has just passed and the day to come. Fittingly, our video installation has no beginning or end, hopscotching cyclically through the temporal flows of a day and night around the world. We aim to decentralize and destabilize the flâneur, itself a modern form, and arrive at a more disorderly yet inclusive outlook.

To return to the hybridity is to remind ourselves of the fact that we need to live in a hybrid world. We cannot imagine a better future, we cannot create a ‘new image of the human,’ until we have come to terms with the irrepressible demands of the world we have already created. U-TT returns constantly to the cultural hybrid notion, not to dream of utopian forms, but to grapple with the reality of our cities in an effort to improve them. Hybridity is about claiming a right to the present, for only through this assertion can one claim the right to move forward.

Film and photography, for us, have always served as important bridges. These media can close the gap between thinking and doing, while connecting the real with the imaginary. As an interdisciplinary collective concerned with urban development, we at Urban-Think Tank (U-TT) have turned toward visual communication as a connecting force between modes of thought and action that too often seem oppositional within our work—theory and practice; scientific research and art; planning and improvising. Of the many modes of visual communication in the past century, films and photographs have at times exerted a hegemonic influence over how cities are envisioned and perceived.

This may be changing as the Internet, and particularly its mobile distribution, rewires what it means to be urban. But even amidst the rise of new and social media, we are still living in a time when visions of our past, present and future cities are informed primarily by the framing of a lens or our cinematic proclivity for packaged narratives. In short, by virtue of being urban creatures, we are also cinematic creatures. If our modern cities make us as much as we make them, then both could be described as having developed at 24-frames-per-second for the past 100 years. As city-makers, it seems only logical that we seek to understand and make urban films. And to do so thoughtfully requires questioning the thematic genre.

In a passage contained in his series of meditations on the Paris Arcades, Walter Benjamin considered the possibility of what the urban film might be: “could one not shoot a passionate film of the city plan of Paris? Of the development of its different forms in temporal succession? Of the condensation of a century-long movement of streets, boulevards, passages, squares, in the space of half an hour? And what else does the flâneur do?” An important question arises when reading Benjamin’s fragmentary remark on how one might use filmic techniques to capture the city. “What would such a film really look like?” It’s a question we are exploring through our video and photographic works.

It’s easy to imagine a flâneur with a camera, much like Vertov, walking around the city and capturing the rapid pace of urban life. Benjamin’s proposed film, Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century, would tell its narrative through an active engagement with the architecture of the city: buildings, streets, boulevards, arcades and stores. The “shock effect” of such a film, Benjamin implies, would make architectural criticism active—accessible for consumption and engagement by an attentive public. We also seek this goal.

While Benjamin never made his film on Paris, his figurations on the flâneur have opened up numerous possibilities for re-conceptualizing urban representation through visual media. By the mid-?1920s, filmmakers of all varieties were producing works known as “City Symphonies,” pushing the genre in both documentary and artistic directions. Often, the classical City Symphonies' focus emerged as a celebration of urbanity, though with an effort to portray its depth (hence "symphony"). These films sought to be self-consciously theoretical and encouraged an active audience. In narrative works, the status of a protagonist within/against the city has been a central premise in a number of film movements, including the gangster film, science fiction, film noir, Italian neo-realism and the French New Wave. Popular examples of this trend can be found in films such as De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1950), Kubrick’s Killer's Kiss (1955) or Godard’s Alphaville (1965). Indeed, the urban film as described by Benjamin has been achieved cinematically to varying degrees of formal, aesthetic and theoretical interrogation 4.

Our video works are contemporary realizations of this visual genre. Perhaps best described as "urban poetry" of the modern world, our movies often also fit into the ignored genre of the “theory film” as works that not only contain theories, but also are often structured around them. Given U-TT’s overarching focus on informal urbanism and socially-oriented design, the same theories that direct our research and practice also guide the conception, production and editing of our videos. We strive to create new discursive spaces in order to raise questions about how cities are shaped and for whom.

We also suggest that more urban films and photographs should be attuned to notions of territory once considered to be on the global margins. In Benjamin’s time, cities were globalizing in the North. Today, it’s in the South. Since we first picked up video cameras 15 years ago, we saw a flâneur’s greatest relevancy not on the sidewalks of Paris, Berlin or New York, but rather the streets, footpaths and rooftops of Caracas, Johannesburg or Mumbai. These metropolises once considered to be the periphery are now becoming the center—the center of population growth, social influence and economic potential. As a collective seeking to understand, shape and communicate a common urban future, we have found ourselves increasingly turning on our cameras around the world and repeating the axiom, “Mumbai is everywhere.” To see our editing and printing room is to witness this psychological—rather than geographic—perspective.

Think of Mumbai not only as a city but as a concept for living—as a theory—is the demand that society renegotiate the relation between order and disorder. The great flaw of the 20th century modernist planning movement was to place an undue amount of faith in the human ability to comprehend rationally the future histories of cities—their forms and social needs. Cities, as it turns out, give rise to disorder. It is only through a measured acceptance of chaos and difference that planners have improved the ways in which we dwell and create. Order and Disorder do not exist despite each other, but rather with each other. Filmmaking and photography help us observe and communicate this relationship in a way that static maps, drawings and diagrams cannot.

Right now, architects and urban designers are suffering from a lack of vision. New technologies have given us powerful tools, but the legacies of those who populated our disciplines weigh too heavily upon our imaginations. Many of our teachers and their teachers burden our conceptual framework from proposing—let alone advancing—radically new designs. We see too many of the same tired forms masquerading as content, decorating cities rather than changing them. We believe documentary and artistic images can help to break this stasis. Benjamin once proposed that what interests humans the most is not the past, present or future, but rather the recent past. In our visual archive of the recent past—focused on the global, urban South—we aim to seize popular interest and inspire a form of criticality that looks beyond the existing and toward the possible.

2 Walter Benjamin, “Das Passagen-Wek,” Vol. V, 1 of Gesammelte Schriften (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1982), p.135.

3 These included documentarian Dziga Vertov, the impressionist Walter Ruttman and even the cubist Leger.

4 Contemporary versions of the City Symphony, often embedded within narrative productions, can also be found in filmmakers such as Woody Allen, Wim Wenders and Spike Lee among others.

About film:

“Mumbai: Maximum City under Pressure” is a film by Urban-Think Tank (U-TT)”, produced by Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner of U-TT, a multi-disciplinary design practice dedicated to high-level research, design and films on a variety of subjects such as contemporary architecture and urbanism.

Mr. Brillembourg was born in New York. He received his Bachelor of Art and Architecture in 1984, and in 1986 his Master of Science in Architectural Design from Columbia University. In 1998, he founded the Urban Think Tank in Caracas, Venezuela. He is a member of the Venezuelan Architects and Engineers Association and the Swiss and Norwegian Architects Association. Brillembourg has been a professor at the Graduate School of Architecture and Planning, Columbia University, where he co-founded the Sustainable Living Urban Model Laboratory (S.L.U.M. Lab). He has over 20 years of experience practicing architecture and urban design. From 2010 - 2019 he held the Chair of Architecture and Urban Design at ETHZ. In 2019 he was invited to become part of GRIP institute at the University of Bergen and he has received the 2010 Ralph Erskine Award, 2011 Gold Holcim Award for Latin America and 2012 Silver Holcim Global Award for their innovation in social design, and the 2012 Venice Biennale of Architecture Golden Lion. His Empower Shack Housing project was shortlisted as exceptional new buildings in world by RIBA 2019 and in 2022 by the Aga Khan Foundation.

Urban Think-Tank can be reached at: info@uttdesign.com