Sensory Translation of Spatial Design

Human perception of this world is a cumulative reaction of all its senses. Without the sense of vision, hearing, touch, taste and smell, life would be tasteless, odourless, and colourless. Simply put, without our senses, the world would not exist for us.

Architecture today, is not just a product of just needs. It has risen itself from the barriers of function alone and now become more powerful and expressive. Still, as we move around the city, we see those typical prototypes of structures that refuse to cause any stimulation in our minds or generate a specific mood. Architecture has been usually is regarded as merely a visual retreat and that needs to be transformed.

Power of architecture

Architecture has the power to make people manoeuvre around the way the architect wants them to and make them feel the space as per the architect’s will. Different elements can penetrate a vibe through the users’ minds and make them react in a particular way. Even the smallest design or structural feature can have a huge impact. For example, having a window view with natural light coming in, helps patients recover faster as compared to patients in a room with no natural light and no window view, according to R. S. Ulrich.

Figure 1 Sensory Architecture

Architecture when designed keeping in mind the stimulation of all sensory organs, can empower the space and bring harmony between the environment and the user. This tool has much more to offer than just shelter. It has the capability to provide peace and also cater to various emotions.

Sensory Design

Figure 2 Architecture and the Senses

Sensory design is human perception, memory and imagination intertwined together, to give recognition to the design and experience of the space. Its main focus is on the occupants, and how the occupant’s sensory stimuli in the built environment can be arranged to lift the quality of life and experience for them. Exploring each sense and its effect in the design, highlights the ability of our brain in interpreting spaces. “Traditionally, there are 5 main senses—the sense of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and the sense of smell. Other senses can be added to the list, such as the sense of temperature, pain, and what is sometimes called the kinaesthetic sense, which informs us about the movement and position of the various parts of our bodies” said Maclachlan (a renowned Philosophy Professor) in his papers called the ‘Philosophy of Perception’ in 1989. Though each sense has a unique character, it possesses equal power to help the user interpret a space differently.

Effect of Senses in Interpreting Architecture

Figure 3 Perception of Spaces

Our ability to feel the texture of materials such as concrete, marble, glass, earthen pots differently, our ability to differentiate the appearances of various objects, our ability to smell different items and associate a memory with it comes so naturally to us, that it is often taken for granted. Our senses make us aware of the environment we are in. Together, they can be called an information-seeking system in which the sense of touch, smell and taste provide for the potential to heal in the immediate space around the user, whereas vision and hearing help us identifying objects and events from a greater distance.

Visual stimulus

The architectural practice is traditionally dominated by eye-sight and the main focus is usually on building aesthetically pleasing structures. The feeling of safety and comfort in libraries and the feeling of anxiety and worry in the reception area of a structure are all due to the visual effect of spaces.

Designed by Tadao Ando, the Church of Light’s most prominent feature is the cross-shaped aperture, the only source through which the light enters, making it visually stunning and powerful. The light entering makes the reinforced concrete structure a space of darkness.

Figure 4 The Church of Light by Tadao Ando

Another great example of visually stimulating architecture is Japan’s “Art Island”, home to a timber-clad building. Here, Tadao Ando focuses on how the essence of light and darkness can be incorporated to create truly powerful experiences. Here, James Turrell’s “Backside of the Moon” which contains a pitch-black space that is difficult to process initially, but eventually the eyes adjust to the grey light installation, and the space starts making sense. It is built in the art house Minamidera where a series of turns take you away from the light into a dark corridor. The visitors feel a sensory emptiness until their eyes adjust and the feeling of disorientation and fumbling fades.

Figure 5 James Turrell’s “Backside of the Moon”

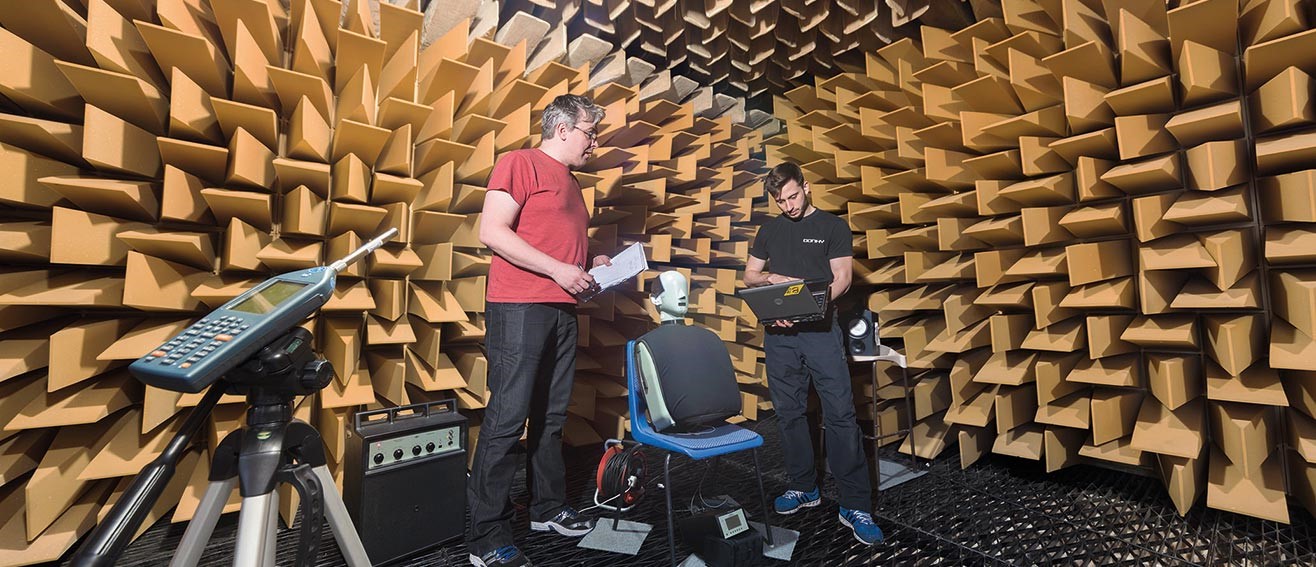

Aural Stimulus

Sound has a much larger role in the impression of a space in the human mind. This is because sound is perceived at a less conscious level than visual information. Sound is very important in recalling memories. These characteristics can be used in the design to create soundscapes to soothe the user’s frame of mind. Some beautiful examples of aural architecture include The Whispering Gallery at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, where the property of sound to travel through media is used, Anechoic chamber at South Bank University, London, to create a sense of hyper-awareness where you can feel and hear your own heartbeats and blood pumping loud, and the Sea organ in Zadar, Croatia that creates music because of the splashing waves. Each of these spaces evokes a completely different emotion and has a completely different motive.

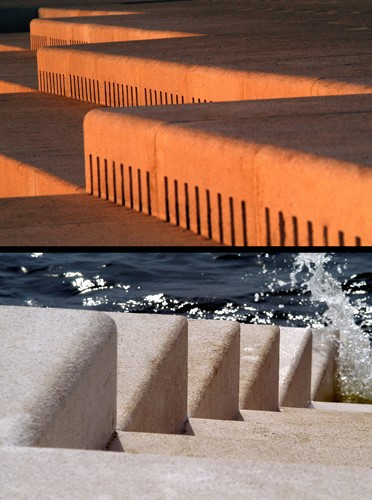

Figure 6 Sounds of the sea, Sea organ, Croatia

Figure 7 Sea organ, Croatia

Figure 7 Sea organ, Croatia

Figure 7 Sea organ, Croatia

Figure 8 Whispering Gallery, St. Paul's Cathedral

Figure 9 Anechoic Chamber

Figure 9 Anechoic Chamber

Olfactory Stimulus

The sense of smell is universal, however, the emotions it evokes vary from person to person. The nose, a powerful memory generator, helps bring back memories with just a small trigger (a sniff!). The memories in the mind are flooded with the visuals associated with the specific smell. Different scents affect the moods, work and behaviour of people differently – for example, the odour of ammonia or other irritating odours cause discomfort in people, whereas the scents of perfumes make us feel pleasant and happy (source:thescientificamerican.com).

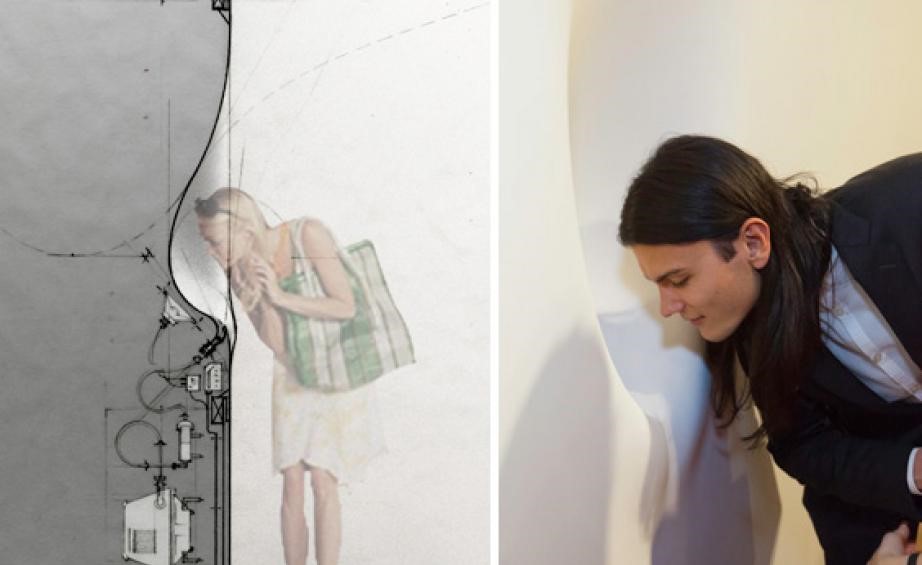

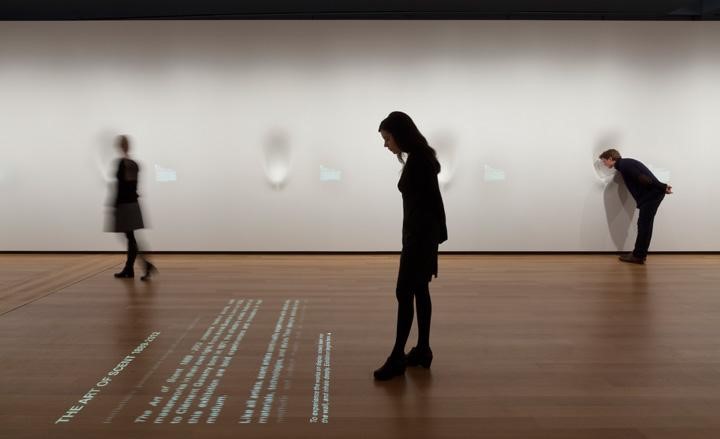

Figure 10 The Art of Scent, Museum of Art and Design

The Art of Scent, Museum of Art and Design, New York City was launched as the first major exhibition to focus on the sense of smell and use it as an artistic medium by DS+R. The museum contains invisible artworks but has distinct fragrances in the walls of the gallery, aimed to evoke memories and affect the thought patterns of visitors.

Figure 11 The Art of Scent Museum as an artistic medium

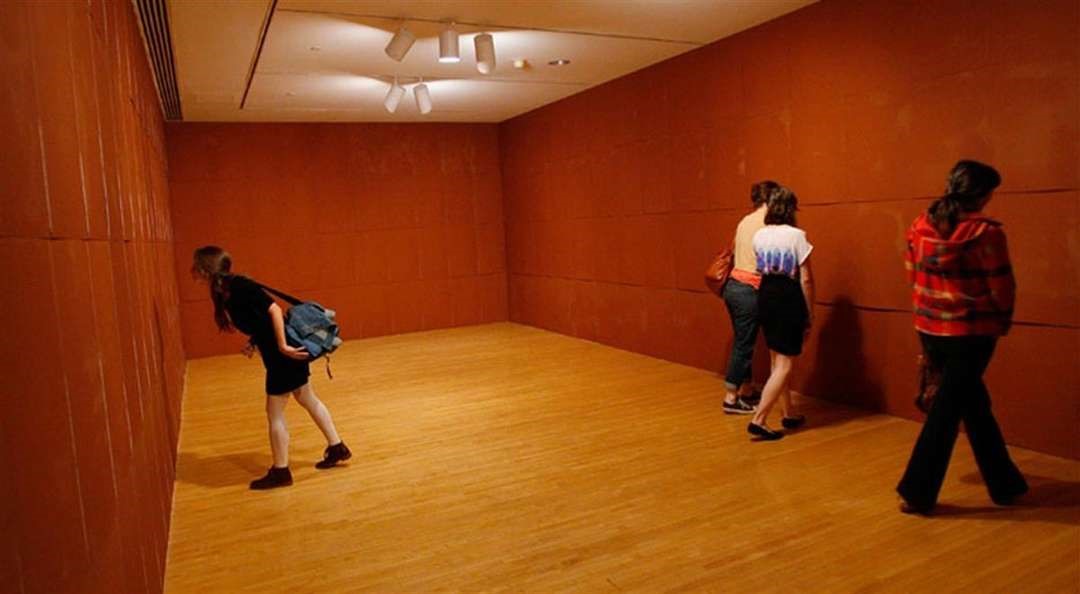

Touch stimulus

The sense of touch is gaining prominence in architecture with the advent of computing technologies (mobile phones to table-top devices). When talking about touch, it’s not limited only to the hand but the entire skin surface of the human body. The tactile interaction of the human body has a lot of potential for creating interactive surfaces in architecture or architectonic elements – walls, floors, and ceiling. Touching a rough or bumpy surface makes people empathise more since they feel discomfort and it helps them understand the discomfort of fellow beings whereas touching a smooth surface makes us feel good (source: thedailymail.co.uk).

Figure 12 Hazelwood school, Glasgow

Figure 12 Hazelwood school, Glasgow

Architect Alan Dunlop, designed the Hazelwood School in Glasgow, specifically for children who are “dual sensory impaired” (both blind and deaf). This makes the sense of touch the most crucial element in making the children gather a sense of independence. The interior walls of this school are multi-textured – that is there is a use of multiple textured materials, which the students can follow with their hands. This will help them get an idea about their whereabouts within the school with minimal help. Despite the challenges they face, these textured walls will increase the children’s confidence.

Figure 13 Top View of the Hazelwood School

Taste stimulus

Juhani Pallasmaa, a well-known architectural theorist, writes “The suggestions that the sense of taste would have a role in the appreciation of architecture may sound preposterous. However, polished and coloured stone as well as colours in general, and finely crafted wood details, for instance, often evoke an awareness of mouth and taste.” To incorporate taste stimulus is to make the user taste the materials and the textures without actually using the tongue.

A Latrobe Fellow and founding president of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, John P. Eberhard, in his book ‘Architecture and the Brain’ artfully says, “You may not literally taste the materials in a building, but the design of a restaurant can have an impact on your ‘conditioned response’ to the taste of the food.” The taste of a place is mostly associated with the function or its speciality – like restaurants, bakeries, hospitals, taste of a city based on its food speciality and so on. This is what the sense of taste has to do with architecture. It is rather deep and challenging for implementation, yet important to give the user a complete experience.

Figure 14 The Chocolate Room, American Pavilion, Venice

Figure 14 The Chocolate Room, American Pavilion, Venice

The Chocolate Room, American Pavilion, Venice was created for the 35th Venice Biennale in 1970 by American artist Edward Ruscha. The wallpaper of the Chocolate Room was made using Nestlé chocolate sheets that were silk-screen printed. He used 360 such Chocolate sheets for the room. This installation forces the users to ponder about the link between taste, euphoria and architectural experience.

Other secondary senses

Texture, temperature, as well as the weight of materials, tend to affect our emotions and behaviour. This is why concrete gives us a feeling of brutality and wood, a material that evokes feelings of warmth and comfort. The brightness, saturation and hue of light and colours in a space have a psychological and physical impact on the health and well-being of humans. Darker colours are preferred in places that require warmth and shades of blue and green are associated with peace and calm. Too bright a light, is seen to cause a feeling irritability and headaches in the occupants, whereas natural light makes the users happier (source: theraspecs.com).

Dual Sensory Designs

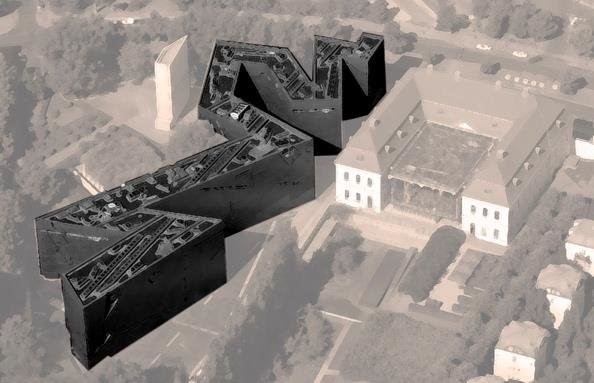

Figure 15 The Jewish Museum, Berlin

The Jewish Museum, Berlin is a strong example of sensory architecture. The building has a titanium-zinc façade in a zig-zag shape. The walls are angular and it features underground axes and concrete “voids” without any heat or air-conditioning. This design by American architect Daniel Libeskind focuses on “Between the Lines”. He did not want to simply design a museum building, he wanted to recount German-Jewish history which is why he created voids in several parts of the building. These empty spaces extend vertically throughout and are a representation of the absence of Jews from German society. The Memory Void contains over ten thousand faces covering the floor over which the visitors walk. The jarring clanging sounds of the metal faces echo in the voids creating an eerie atmosphere. These interactions and sounds affect the visitors and many people are left with feelings of insecurity or disorientation (source: fotoeins.com).

Figure 16 The memory void, Jewish museum

Figure 16 The memory void, Jewish museum

Researchers working in the field of environmental psychology have stressed quite often about the impact of sensory features of our environment on humans. The impact of our built environment is both positive and negative. However, if not designed correctly, the built environment around us can take a toll on our health and peace of mind. The extensive use of windows in tropical climate regions leads to heating up of the atmosphere and ultimately global warming. Similarly, the failure to incorporate aural factors may explain some part of the global health crisis associated with noise pollution, which interferes with our sleep, health and wellbeing.

A commentator writing in ‘The New York Times’ (Opinion| Scent and the City : Dated 27th October 2013) says, “While these findings have obvious implications for health care, the opportunities for architecture and urban planning are particularly intriguing. Designers are trained to focus mostly on the visual, but the science of design could significantly expand designers’ sensory palettes. Call it Medicinal Urbanism.”

A multisensory approach incorporated in the development of spaces is thus, the way forward. Also, there is a need to promote awareness of sensory architecture for social, cognitive and emotional well-being. As, in a world where there are already pressing environmental issues, the built environment shouldn’t add to them!

About Author:

Richa Malhotra is an Architect and prefers to be called a Learner. Her quest for knowledge led her to explore options in varied fields where architectural learning can be useful. Currently a Civil Services aspirant, she is working part time as a Freelance Architectural Writer. She shares her reflections of the world around and works up her mind and creativity by writing about them. She’s on the path to exploring her potential further and looking at expanding her scope of work. Her main aim in life is to never stop learning, upskilling and practicing!

She can be reached at: richam31@gmail.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/richa-malhotra-/

Reference Links :

4. https://www.coa.gov.in/show_img.php?fid=148

– page 10,11

5. https://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/1522

6. https://arts.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Pallasmaa_The-Eyes-of-the-Skin.pdf

- page 67,68

7. https://medium.com/@holos.design/architecture-and-the-senses-35b7dc1c0a82

9. https://www.metropolismag.com/architecture/multisensory-architecture-design-history/

10. https://www.cwejournal.org/vol10noSpecial/considering-the-five-senses-in-architecture/

11. https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/the-architecture-of-perception/

- for examples

12. https://cognitiveresearchjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41235-020-00243-4