The Political Capacity Of Architecture

Decoding the symbiotic relationship between architecture and conflict and advancing the agency of architecture towards positive peace

As the Doomsday clock ticks ever so close to the dreaded hand of midnight, the world rests on a fragile sense of anxiety and hope. Anxiety of a day when the brittle relations may spill over and give way to full-blown chaos; hope to push the former by at least a day onto the morrow.

As humans, the deposition of whether violence is inherent in our nature is still a divisive debate. The reality is that conflict is an everyday global happening. It has become the norm. But why does there seem to be a significant ignorance to this in the world of architecture? “Isn’t it … [because] most people aren’t in conflict zones which means if you are unaware of the problem, you don’t seek it out and that’s why the design community at large is addressing other issues?” (Humeid, 2019). Have we become so detached from this actuality that we cannot cause to affect it? Have we - in due course - forgotten that the birth of architecture was to serve man to find a better tomorrow? Or was it ever? Does architecture have a malevolent origin and is this still replicated in modern times?

‘Guernica’ remains one of the most moving and powerful anti-war paintings in history

Guernica, Pablo Picasso, Oil painting on canvas, 1937

The Foundational Myths of Architecture and its Contemporary Branches

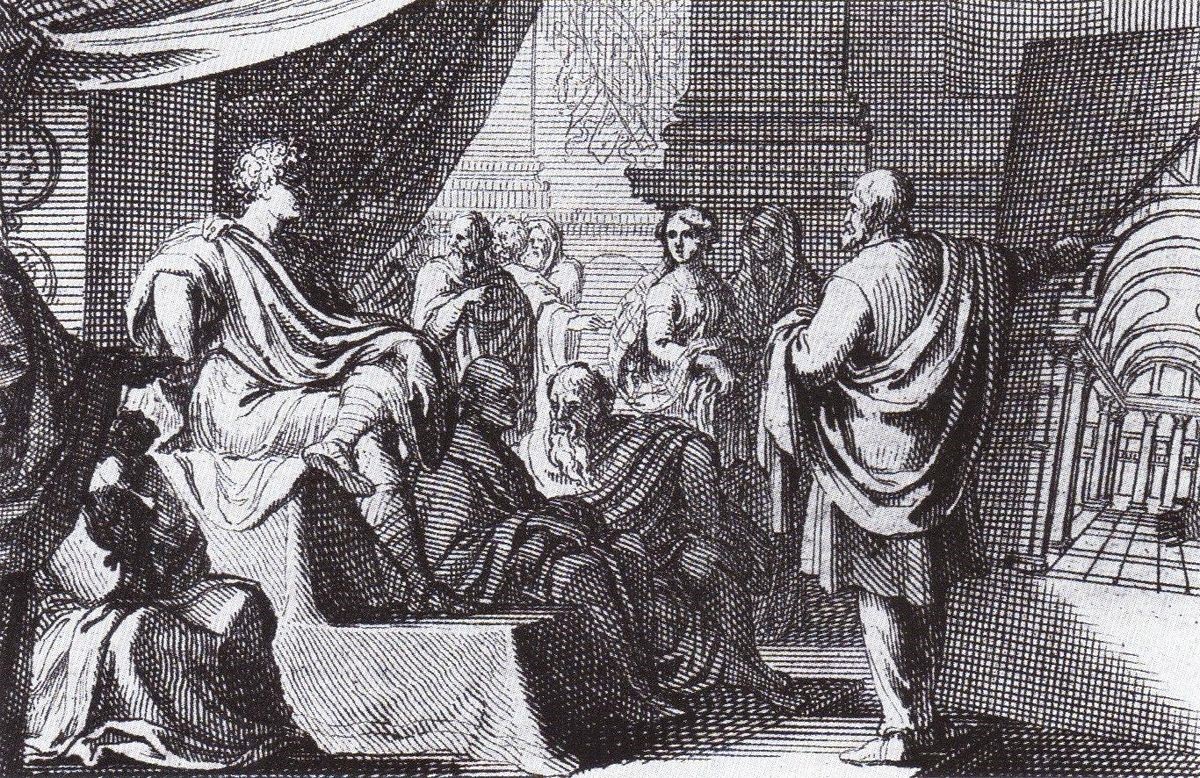

Vitruvius’s De Architectura is considered to be the first treatise in architecture. This collection of 10 books was presented to Emperor Augustus more than two millennia ago and has since been taught as the foundational classical text that marks the formation of western architecture as a discipline. But what is less known is the agenda to write the book was largely shaped by a project of world domination as explained by Indra Kagis McEwen in her book ‘Writing the Body of Architecture’. An example is the ancient town of Timgad in present-day Algeria which follows the grid plan and “represents a remarkable example of a Roman military colony which was created ex nihilo (AD 100). It follows the guidelines of Roman town planning, a remarkable grid system… which is still used today... the basis of this model [being] the military encampment” (Docevski, 2015).

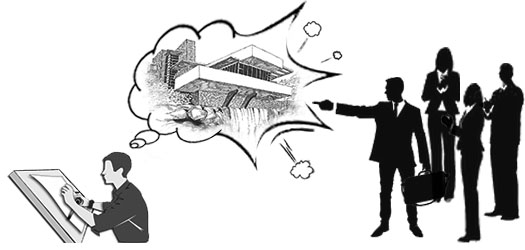

A 1684 depiction of Vitruvius (right) presenting De Architectura to Emperor Augustus

Sebastian le Clerc, 1684

Ancient Roman city built on the model of the military camp,

Timgad, Algeria, AD 100,

George Steinmetz, 2012

The modern branches of this architecture reveal an architecture of expansion that was practised by architects under Nazi Germany with their GENERAL PLAN OST with an aim of ‘GERMANISATION’ of Eastern Europe. Similarly, during the Cold War Era, ‘SOVIETIZATION’ was practised where countries under USSR were prescribed certain architectural and city planning models to follow. An architecture of domination is visible in the proposed WORLD CAPITAL GERMANIA that resembled Roman models. The late 20th and early 21st centuries are no exception to this rule. Evident in both Tibet and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, the spread of [colonial] settlements has completely changed perceptions that the population has of its environment... the feeling of dispossession of places and landscapes is strengthened by the superimposition of an alien spatial and historical narrative, in which historical references and places of collective memory are renamed, reinterpreted, or suppressed” (Piquard & Swenarton, 2011). Another example is the rise of far-right groups such as Identity Evropa that have weaponised classical architecture and embarked on a culture war to redefine what - and who - is ‘authentically’ European (O’Brien, 2018).

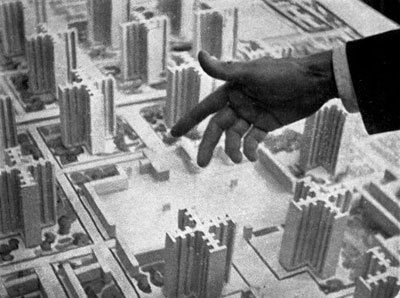

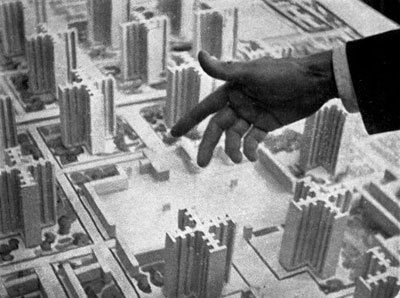

A model of Adolf Hitler’s plan for Berlin formulated under the direction of Albert Speer, looking north toward the Volkshalle, 1939, German Federal Archives

Did the principles of firmitas, utilitas and venustas carry an undercurrent of architecture that was fixated on expansion and world domination? And if so, hundreds of years later, has this language finally evolved and branched out to - of many others - an architecture of democracy, inclusion, and diplomatic benevolence? Rather hauntingly in ‘Inside the Third Reich’, Albert Speer wrote, “By using special materials and by applying certain principles of statics, we should be able to build structures which even in a state of decay, after hundreds or (such were our reckonings) thousands of years would more or less resemble Roman models” (Cohen, 2011).

The liaison between Architecture and Conflict/War

Architecture and the built environment are among the first victims of conflict and war. “[Due to the] extent to which a people’s identity is linked to architecture… such destruction not only shatters a nation’s culture but can be a deliberate attempt to eradicate the cultural memory of peoples and nations” (Bevan, 2005).

But there exists another relationship between architecture and conflict/war. That of an anomalous symbiotic liaison in which one seems to feed on the other and thrive. Conflict and war have not only given birth to an architecture of imposition but have also propagated architectural innovation and stylist movements. On the other hand, elements of architecture - in the tangible forms of walls, housing, and religious edifices to name a few - have been used across the globe to separate, segregate, and impose violence.

An Architecture towards Peace

The last century was the bloodiest and most destructive century in human history. The false promise after each conflict/war was there would never be another; this century slowly seems to tread through similar patterns. Conflict seems inevitable, but it would be presumptuous to say that architecture has stayed quiet in the face of strife.

“…emergence of new spaces of conflict considerably altered architectural discourse as extreme conditions of war, militarization… were (and still are) threatening to structurally reconfigure our living environments… these urban intrusions seem to have produced a diversified field of thinking and action in architecture…architectural practices have shown a remarkable adequacy in addressing spaces of conflict, crisis, and disaster” (Schoonderbeek & Shoshan, 2016).

Discourse on an Architecture towards Peace

The post-war recovery in the last century required the extensive presence of architecture and its disciplines since the built environment was among the worst wounded. Many movements and architects jumped into this foray to positively (or at least they hoped) exploit the situation and possibly render meaning to “Existenzfragen, ‘the questions of existence’” (Crowley, 2008).

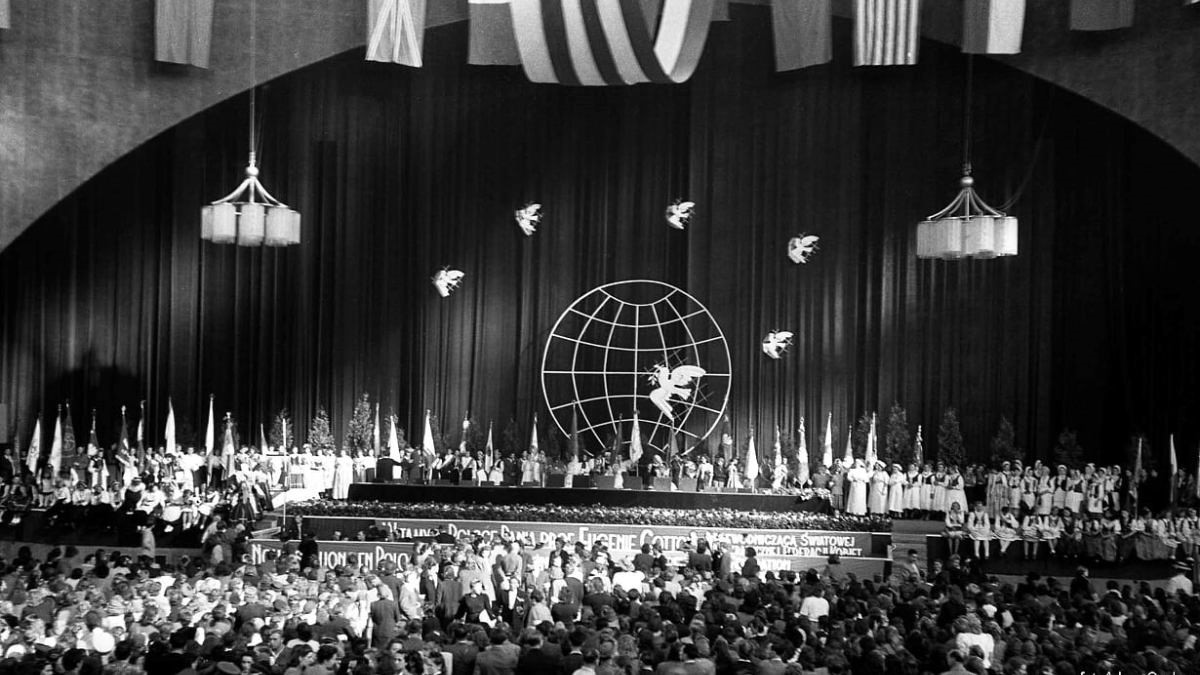

“congress in action”, The World Peace Movement

Wroclaw, Poland, 1948

The City Museum of Wroclaw archives

During the Cold War, intellectuals including architects assembled at the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defence of Peace in Wroclaw (1948) to deliberate the future of the world, but the program ended on a disappointing note due to its pro-Soviet stance. However, along with the ‘Exhibition of the Regained Lands’ (Wroclaw, 1948), it had a significant effect on the rebuilding process in war-torn Poland (Crowley, 2008). The UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) along with other humanitarian bodies have also funded/developed architecture in places of conflict.

But the aim is to zoom further and discover specific entities that have had a fervent focus on architecture and peace.

Architecture sans Frontieres in action Building Communities, Salvador da Bahia

Brazil, 2009-10

ASF, UKx

‘Architecture for Peace’ is an Australian-based NGO (2003) with a motto of “…urban expertise with peace as our goal” and has completed projects in Uganda, South Sudan, and East Timor. ‘Architecture san Frontieres’ (1979) is an international operation focusing on the Global South with a goal to “enable access for vulnerable communities to architectural services… in order to increase resilience and reduce vulnerability.” The ‘Architects without Frontiers’ founded by Esther Charlesworth (1998) focuses primarily in the Australia and Asia - Pacific region. A book by the same name was published that emphasizes the “political and aesthetic criteria required for rebuilding after war and calamities.”

Design Like You Give A Damn

Part II, 2010

Cameron Sinclair_Architecture for Humanity

Football for Hope Center

Kimisagara, Rwanda, 2009

Architecture for Humanity + Killian Doherty

‘Architecture for Humanity’ was a US-based charitable organization founded in 1999 that published two parts of the book ‘Design Like You Give A Damn’ which recounted architectural projects (including theirs) around the world that addressed humanitarian crises. ‘Architecture of Peace’ is an international research and action project based out of Amsterdam and Berlin that deals with interventions at all scales of architectural capacity. Two editions of the Volume magazine have been dedicated to their work. ‘Design and Peace’ was a colloquium organized by the Alvar Aalto foundation (2019) to have a collective examination on the topics of “conflict and peace, peace in society, and spatial peace”. ‘Architecture of Democracy’ was a joint online public discussion between the architectural departments of Harvard and MIT on the character of architecture to represent peace and democracy.

“colloquium in action”

Design & Peace

Alvar Aalto Foundation, 2019

In the school of ‘taught architecture’, Political Architecture: Critical Sustainability by KADK deals with “architecture’s role in enforcing, implementing and transforming a particular societal order.” The Master’s degree in International Cooperation: Sustainable Emergency Architecture by the UIC School of Architecture “prepares architects… to rebuild communities affected by the impact of… military conflicts… in both developed and developing countries.”

What | Why: The Agency of an Architect

So, what can an architect do in all of this? What is the political agency of an architect?

“playing god”, Plan Voisin,

Le Corbusier, 1964

source unknown

During WWII, architects and historians were enlisted by the USA to systematically list the objects not to target for aerial bombardment which caused the preservation of churches and palaces… but resulted in a “detriment to the urban fabric” (Cohen, 2011). Hitler’s architect Speer justified his architectural action of the camps at Auschwitz claiming an ‘obsessive fixation on production’ had ‘blurred all considerations and feelings of humanity’ (Cohen, 2011). The French riots of 2005 have been exclusively blamed on the modernist ideology of the ‘Ville Radieuse’. If architects and/or their built environments have the capacity to cultivate violence and discord, can it not be wielded to harvest peace too?

The capacity of an architect is certainly not enough to attain peace - positive or otherwise - but at the same time architecture enjoys a certain privilege over other forms of representation. The privilege of being able to recast space, mould material and create a realm. The use of this privilege is the agency of the architect in a world at conflict. Because it could be through this realm that open dialogue is encouraged, tenets are exchanged, harmonious values are advocated, and goodwill is endorsed.

“Architects as pathologists have the tools to diagnose the fractured urban condition, analysing and prescribing remedies for dysfunctional and often still politically contested cities” (Charlesworth, 2006) who further developed ‘archetypes’ as roles that an architect could or should adopt in places of conflict.

Can a progressive agency of socially responsible architecture finally prove Margaret Crawford wrong when she claimed that “both the restricted practices and discourse of the profession have reduced the scope of architecture to two equally unpromising polarities: compromised practice or esoteric philosophies of inaction”. Is it possible that converting the esoteric to an exoteric ideology that can be pragmatically practised, guide the architectural community to participate in the process of peace-building?

Through the questions raised in this essay, the architectural community should ponder the true extent of the capacity of an architect in a world at conflict and how our design tools can positively affect it. Because it is only through questions that answers be found, and only through answers solutions be.

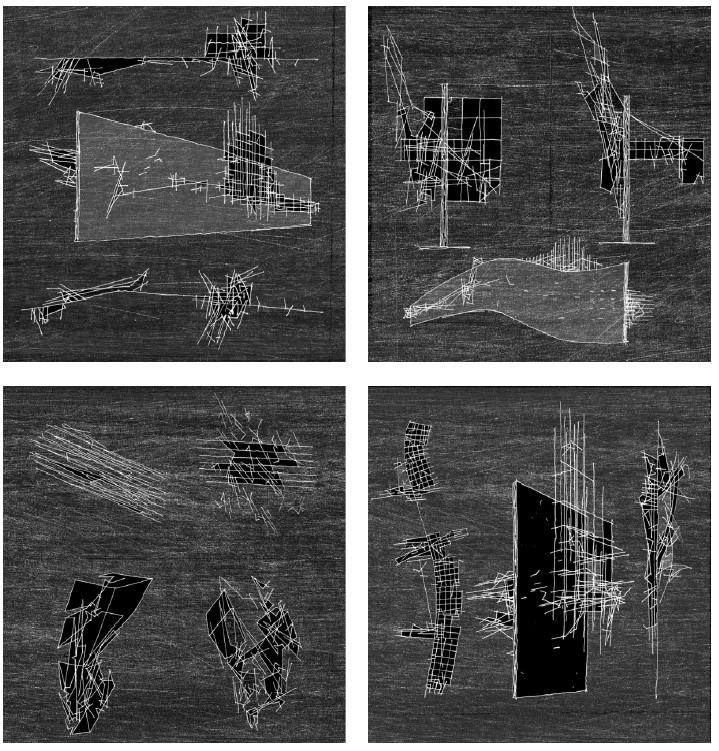

This essay concludes with an experiment on walls by Lebbeus Wood. “The Wall Game uses some sections of the wall as a two-sided playing field... It is a game only for two opposing sides. One side cannot play it alone, as unbalanced structural forces will bring the wall down very quickly... Conversion of a construction occurs when its system of order, that is, its basic system of spatial reference is transformed by the system of order of the opposing side... Even the most bitterly opposed adversaries who learn to play together find it difficult to kill each other” (Woods, 2019).

Wall Games,

Lebbeus Woods, 2019

About the Author

Jose Sibi is an architect and urban designer currently working in Milan, Italy. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and Urban Design from Politecnico di Milano. A firm believer that the discipline of architecture has the great power to not only improve existing human conditions but also create new possibilities for a better tomorrow. As Uncle Ben said, “with great power, comes great responsibility”. And thus, on a perpetual quest to fulfil that responsibility. Author can be reached at: linkedin.com/in/jose-sibi

Bibliography

Humeid, A. et al. (2019) Design & Peace, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Piquard, B. & Swenarton, M. (2011) Learning from Architecture and Conflict, The Journal of Architecture, 16(1), (p.1-13)

McEwen, K.I. (2003) Vitruvius: Writing the Body of Architecture

Docevski, B. (2015) Timgad The Lost City: A 2000 Year old Roman City With Surprisingly Modern Grid Design, Vintage News

O’Brien, H. (2018) How Classical Architecture Became a Weapon for the Far Right, New Statesman

Cohen, J.L. (2011) Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War

Crowley, D. & Pavitt J. (2008) Cold War Modern: Design 1945 - 1970

Samia, H. (2019) War Zones

Bevan, R. (2006) The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War

Woods, L. (1993) War and Architecture, Pamphlet Architecture, 15

Coward, M. (2009) Urbicide: The Politics of Urban Destruction

Pryce, G. (2018) Peace Walls and other Social Frontiers can Breed Crime and Conflict in Cities, The Conversation

Allweil, Y. (2017) Homeland: Zionism as Housing Regime, 1860–2011.

Kripa, E. & Mueller, S. (2020) Fronts: Military Urbanisms and the Developing World

Stephen. G. (2010) City Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism

Al Sabouni, M. (2017) From a model of peace to a model of conflict: The effect of architectural modernization on the Syrian urban and social make-up, International Review of the Red Cross (2017), 99 (3), 1019–1036, Conflict in Syria

Volume (2010) Architecture of Peace, 26

Volume (2014) Architecture of Peace: Reloaded, 40

Schoonderbeek, M., & Shoshan, M. (Eds.) (2016) Spaces of Conflict, Footprint, 10(2)

Charlesworth, E. (2006) Architecture without Frontiers: War, Reconstruction and Design Responsibility

Alvar Aalto Foundation (2019) Design and Peace

Crawford, M. (1991) Can Architects be Socially Responsible?, Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture, Seattle Bay Press, pp. 27-45

Sinclair, C. (2006) Design Like You Give A Damn: Architectural Responses To Humanitarian Crises

Sinclair, C. (2012) Design Like You Give a Damn [2]: Building Change from the Ground Up